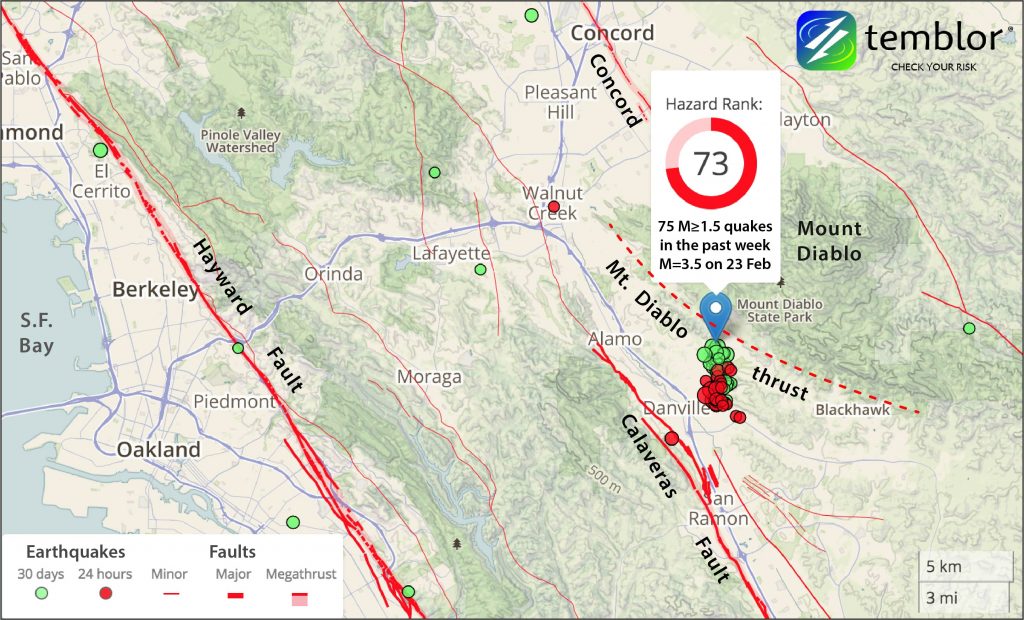

75 quakes have rattled the beautiful town of Danville – you remember ‘Mrs. Doubtfire’ – last week? The shallow quakes hit at a depth of 5-7 km (3-4 mi) on a unmapped fault or set of faults. Although most of the quakes in this week’s swarm are 3-5 km (2-3 mi) from the Calaveras Fault, the swarm is clearly migrating toward the major Calaveras Fault.

With a slip rate of about 15 mm/yr (0.6 in/yr) and a length of about 100 km (60 mi), the Calaveras is highly active and certainly capable of a M7+ earthquake. The fault cuts through the towns of Walnut Creek, San Ramon, Dublin, Pleasanton, Sunol, and Hollister.

The largest historical quake on the Calaveras Fault was a M6.6 earthquake in 1911. At that time, most U.S. seismic observatories were run by scientist priests at Jesuit universities. But by the time these professors began to die in mid-century, their lifelong seismogram archives were thrown out. Only one 1911 seismogram from the U.S. survived, from the University of St. Louis, which was saved by Prof. John Ebel, former director of the Weston Observatory of Boston College.

Swarms likely light up portions of faults that suddenly begin to creep or slip at a much higher rate than usual. Some 600 quakes struck San Ramon, also near the Calaveras Fault, in October 2015. Another swarm struck the central portion of the Calaveras Fault in April 2016. But neither triggered a larger shock. Most faults do not creep at all, but parts of the San Andreas, Hayward and Calaveras all do. Why faults start and stop creeping is a mystery, but most swarms and creep events do not cascade into larger earthquakes.

Nevertheless, should this swarm penetrate the Calaveras Fault, the chances of a larger shock will climb, and the monitoring vigilance will intensify. If you live or work in the East Bay, this is the time to ask yourself if you are quake ready. This means having an emergency kit and plan, securing your contents, retrofitting an older home, and considering insurance

0 comments:

Post a Comment